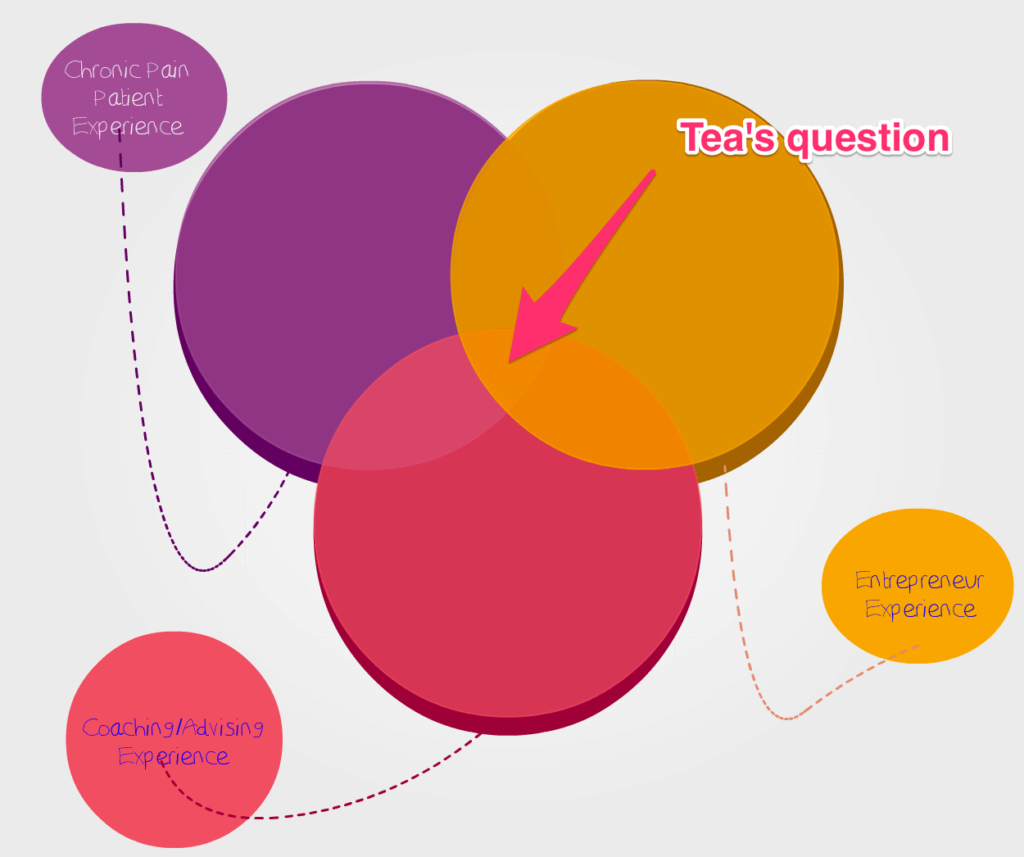

I was asked to share the infographic in this post, and I decided to do so. I think there’s some information contained in it that could be helpful to some readers, and that’s pretty much my main criteria for whether or not to share something under the Euston Arch banner.

So, yep, thar she blows, and enjoy.

However.

I have … thoughts.

And y’all know me. I’m not genetically capable of being quiet.

So I’ve also shared those thoughts beneath the infographic. Please note those are my (considered, educated, but strictly personal) opinions, and not those of the infographic’s creator, that site, or anyone associated with that site. Mine, and mine alone.

First though, as with any new resource I share, I want to give a few warnings:

- Every chronic pain experience — and condition — is different. Your experience may not correspond to someone else’s, even if that person has the same diagnosis as you do.

- As with any new treatment modality or suggestion, whether it’s prescription medication, conservative, or surgical, please check with your own primary care physician first.

- Your PCP can tell you whether the suggestions in this graphic are a good idea for you, given your specific condition and treatment plan, and how to proceed safely.

The Infographic

Annie’s Thoughts on Exercise and Chronic Pain

The big problem with any blanket recommendation to chronic pain patients to “Just exercise more!” is post-exertional malaise. One researcher called PEM “an illness within an illness,” and I think that’s about as accurate a metaphor as any you’ll find.

PEM hits people with a variety of CP-related illnesses, one of the most common being ME/CFS (or “chronic fatigue,” as some erroneously refer to it). Fibromyalgia also carries an increased risk of post-exertional pain and malaise.

And what you may not know is that even though PEM is a self-reported symptom, and thus treated just as skeptically as any pain, researchers have actually proven it’s real .

PEM isn’t simply the muscle soreness healthy individuals often experience after exercise. That soreness is a normal physiological response. PEM is wholly different. It usually represents a worsening (sometimes significantly so) of already existing pain levels.

And it’s triggered by exertion – i.e., by exercise. Hence, the name “post-exertional malaise.”

(Although to be honest “malaise” always sounded to me like something a Victorian gothic novel’s heroine would complain of, shortly before sinking ever so gracefully onto her damask fainting couch in a swoon. I dunno. Maybe that’s just me. PEM ain’t for wusses, in any event.)

So that’s my first problem with this infographic: Exercise can make your pain worse for many of us, and that’s not mentioned anywhere that I can see.

There is one sentence that acknowledges the possibility of PEM, albeit in a terribly vague, roundabout way. It’s the statement halfway down reading:

If you feel abnormally fatigued or experience more pain than usual, stop exercise until your symptoms decrease, and then gradually start exercising again.

Here, the assumption is that the PEM is itself a rarity, and that when (not if!) it goes away, you’ll be able to resume the very activity that caused it in the first place.

And I’m over here like …

And what’s more, PEM can last for an unknown length of time. Every time you get it, it’s like waiting for the other shoe to drop, for — as one blogger put it ….

Two days? Two weeks? Two months? Two years?

Studies currently suggest that there may be an immune system response behind PEM. It could well be that exercise in FM patients retards the production of growth hormone, which in turn triggers cytokines to prompt increased pain from muscular cells.

So FEM is real, and it can be as distressing – or even more so – than the primary pain caused by the underlying condition.

And, again, just to drive the point home: this is just what exercise does to many people with chronic pain.

“Tough it up and push through the pain” is therefore really crappy advice to give to someone living with chronic pain.

My Experience Exercising With Fibromyalgia and Scoliosis

The kind of exercise that I can do, for example, is nowhere near enough to ward off the detrimental effects attributable to a sedentary lifestyle, according to the medical community.

I can walk for 10 to 15 minutes.

I can do 10 minutes of yoga.

I can handle maybe 5 minutes of ballet barre exercises (plies, battements – but not grand battements – and tendus, that’s it, stick a fork in me, I’m done).

Many days, I can do one of those three things, but not the other two.

On really good days, I can handle all three – but maybe a third of the those really good days are then followed by fibromyalgia flare-ups, which put me flat on my back in bed with a heated-up rice pack for at least 24 hours, and creeping around like a frail octogenarian for 48 hours thereafter.

What am I saying, then? “Don’t exercise, ever”?

No. Of course not.

I’m saying stuff like this infographic can be really aspirational and inspiring for folks like us who have lived with chronic pain, maybe for years, and still miss the active lives we used to enjoy.

But it can also be dangerous.

Life is different post-diagnosis. It just is.

A new reality means that you cannot simply assume the old rules still apply. Rules like “exercise is good for you.”

Because for many of us, it isn’t.

On the flip side, movement has helped me reclaim some of my health, and I cannot deny this fact: Being completely still – for example, during those days when I’m cautiously nursing some painful part of me – also makes my pain worse.

If this is you – if you’re like me, if PEM is a fact of life for you – what I recommend instead of exercise is movement. (Of course, you should always talk to your doctor about this first and get her input.)

Movement is not exercise – at least not the way this infographic seems to define it. Movement is gentle. It’s the minimal amount of activity necessary to no longer qualify for the word “still.”

Get up and move every 30 minutes or so. Take an extended movement break of 10 minutes or so every hour. And when I say movement, I do not mean “aerobic movement.” Or “strenuous movement.”

I mean stand up, if you’re able to.

Walk around the house, if you can.

Walk around the yard or the neighborhood, if you’re that lucky.

Or move your arms a bit. Move your fingers. Move your feet and ankles. Lift your lower leg, straightening it out from the knee, while you’re sitting in your chair. Do that once. If that’s OK and doesn’t hurt, do it another time. Then move some other body part.

Move gently. Move cautiously. And move just a little, especially at first, especially if you haven’t been moving at all.

Do that for a week or so. See how you feel, both immediately after and the next day.

The second week, try doing just a little bit more. One more leg lift. Thirty more seconds of walking.

Is this terribly trying and frustrating? Will it just make you even more keenly aware of what you can no longer do?

Yep, and holy Christ, yes. I won’t lie to you. It sucks a lot.

I used to do 90-minute ballet classes several times a week, for Pete’s sake. Here I am barely able to manage a few minutes of baby ballet at a makeshift barre. I MEAN, C’MON.

But the alternative to moving is not-moving.

You know what else is not-moving?

Death. (Sleeping isn’t even not-moving, because as any parent who’s ever shared a bed with their kid knows, sleepers sometimes move a lot.)

I don’t know about you but I’m not ready to be not-moving. I’ll move as much as I can for as long as I can, but I know my body, and I know when to quit.

Until you get there with your new-reality body, you’ll have to work to learn just where your new limits are, and how to stop just short of them.

But please don’t look at messages like the one in this infographic and think “oh yeah, I should be able to do that.” Or “I can’t do that, therefore I’m truly pathetic.”

Use it instead as a starting point for a discussion with your doctor.

Come to terms with what your diagnosis means for your new physical reality, and then begin to explore – gently – those new borders.