So, as I revealed in the last post, I was forced to move last year.

So, as I revealed in the last post, I was forced to move last year.

I’m sure we can all agree on this point: Moving? Sucks. Regardless of the excitement of new digs, fresh start, all that jazz – it just sucks.

But when you’re living with chronic pain, moving is its own special brand of hell. Things that the normals take for granted – like, say, packing, cleaning, walking – we basically roll the dice on. Will we be able to move that box from the truck to the house? It’s a crap shoot.

Fortunately, I had a fair bit of advance warning. True, the former landlady started out giving me two weeks notice, but ultimately, she was very fair and I ended up having two months, give or take a few days, in which to get ready for the impending trauma.

Sounds perfectly reasonable, doesn’t it?

Two months. I mean – eight whole weeks! That’s plenty of time for us to get our crap together, weed out the stuff we didn’t want to move, arrange for a new place, line up help …

Yeah.

Here’s what actually happened.

Figuring It All Out

The biggest obstacle was the first one I had to face: figuring out everything I had to do in order to accomplish the big-picture goal of relocating.

Now, see, normals just go find a place, get some boxes, start packing, call some friends, order up pizza and beer, and they’re done.

But CP Dolls have additional hurdles they have to clear. Reduced physical capacity means reduced capacity to earn, which means reduced income – in my case, severely reduced income. So, job one was finding enough money to actually accomplish the move.

First month’s rent, deposits for the house and for the utilities, the actual costs of moving – I don’t have a car (I had to sell it a year ago to make rent), so I was going to have to rent a truck – all these expenses totaled up were well beyond my means.

I was incredibly fortunate, and my friends and loved ones were incredibly generous. My brother contributed the truck rental costs. Through a few friends who worked in the social aid community in my area, I found out about a new grant-funded program at our local Section 8 agency that was designed to help folks like me with relocation costs. That program ended up helping me with the deposit and first half-month’s rent on the house.

With a little careful juggling, friends who chipped in generously, and a last-minute website job that came in, I had just enough cash to cover the utilities deposits and hiring some folks to help with the physical labor.

Barely, mind you. But I had what I needed.

So then it was on to the next dragon I had to slay …

Finding Someone Who Was Willing to Rent to Me

Spoiler Alert: This one’s got a surprise ending. Well, it was a surprise to me, anyway.

Refer back to that whole “reduced earning capacity”/“reduced income” thing.

Another unpleasant side effect of living with chronic pain is the poverty that comes with it. And the poverty itself also increases the cost of living. In other words, it costs the poor more to live in many instances.

This particular project, then, would reflect one of those increased costs.

Normals can go out, look at apartments or houses, fill out an application, and generally go on with their lives while making their decision – get that, their decision – of which of the handful of suitable options they want to live in, because of course their applications will be approved.

Why wouldn’t they be? They’ve got healthy-ish bodies and the jobs and (relatively) solid credit scores that go with them.

But when you’ve been struggling with CP for years, and the last several of those years were of the self-employed, cobbling-a-living-together-from-all-your-random-skills variety, then you’ve got a whole different cobble-stoned, obstacle-laden road ahead of you. It looks more like this:

- Call a bunch of places that advertise available space.

- Find out which will accept Section 8 (which you anticipate getting in two to four months, since you’ve been on the waiting list for two years).

- Plot out with military precision the bus routes you’ll need to take to go view the three or four units still on your list.

- Cry, because you realize even with the bus routes you’ll end up walking three miles and you just cannot do it.

- Cry more when the first landlord calls back and says that you took too long trying to arrange transportation and the unit is no longer available.

- Talk to a friend – or more accurately, listen while friend talks you down off the ledge. Dig deep. Somehow, find your resolve again.

- Start all over.

- Find one possible apartment or house, then call the cab and go see it immediately (paying $12 for the one-way trip) and on the way, mentally pep-talk yourself up into your best, most positive, friendly, reliable persona so you can convince the landlord to rent to you despite the fact you’re self-employed and lost an apartment in eviction proceedings four years ago when the world fell in on you.

- Which, by the way, is freakin’ exhausting, so after it’s over, collapse.

Rinse and repeat as needed.

But here’s where the universe surprised me big time: That first cab ride?

Ended in a signed lease.

For a beautiful 900 square foot 2-bedroom 1945-built cottage with hardwood floors.

And despite the lack of heat and the piss-poor water flow, I LOVE THIS PLACE SO MUCH.

(Although I do have to get wi-fi installed. This every-day-trek-to-the-coffee-shop is good for my body but bad for the wallet.)

So, the lesson I took from all that goes something like this: “Plan for the worst, but be open to the possibility that God might throw you a curve ball and really delight you with an unforeseen assist.”

Which left only the biggest, baddest dragon of all …

Actually Moving

“How many times have I moved in my life?”

The question occurs to me as I sit here struggling to come up with the words to describe what happened not even two months ago.

The answer, as near as my fibro-fogged brain can tell, is “24.”

Twenty-four moves.

Is that a lot? ‘Cause it seems like a lot.

I’m including in that tally a move from Chapel Hill back to my hometown when I was six years old, though I left out the move from hometown to Chapel Hill three years prior (because, hello, I was a toddler) and I probably shouldn’t even count this one at all since my contributions consisted exclusively of holding a doll and sitting well out of the way.

And it also includes all the times I moved into and out of a dorm in college – that’s eight moves right there.

That still leaves 13 moves. Yeah, that’s still a lot, isn’t it?

So, let’s go back to the “24.”

For the first 18 of them, I had help.

But the last six?

- Out of mom’s mobile home and into the 100 square foot studio apartment

- Out of that apartment and into a friend’s basement

- Out of that basement and into a friend’s spare room two states away

- Out of that room and up to another basement, in another (now ex-)friend’s house, in the city where I currently live

- Out of that God-awful basement and into two rented rooms in someone’s home

- Out of those rooms and into the rented basement (that’s three basements in three years, for those of you playing our home game)

Without help. All of ‘em. Each and every move was accomplished by yours truly.

And that leads us to this last move – out of that last rented basement and into this lovely cottage.

But here’s the difference between those six and this most recent move, and it’s a pretty damned big one: This time, in addition to clothing and books and toiletries and stuffed animals – little stuff even I can lift – this time, I was moving furniture and a whole kitchen-ful of … er, kitchen crap.

We’d lost all our furniture years before, in two separate waves. The first wave hit after the eviction, when I had to give away or abandon a lot of furniture I just couldn’t fit into that shoebox studio, and the second one crashed months later, when I couldn’t afford to keep up with the storage unit rent for the stuff I hadn’t been able to bear parting with.

But over the course of the last two years in that rented basement apartment, I’d accumulated a somewhat sparse collection: two couches, a loveseat, a table, three chairs, two beds … that’s it, and it all came from donations from other people and giveaways. It was all hard-used and definitely looked like what it was: second-hand crap. But it was my second-hand crap, damn it.

And now it was mine to move.

I called the few male friends I had made who were local, but they all were booked up solid for the Thanksgiving holiday, and couldn’t lend a hand.

Next, I called the contacts I’d made in the local social aid community – they said they’d get back to me but, since it was a holiday, they were all overworked taking care of the homeless population in town.

I even asked the cabdriver who drove me to look at the cottage that first day. He was 72 but, bless him, he said he’d be happy to help – but I’d have to find someone else to help him, and I’d have to do the move on the Tuesday before turkey day, which was two days before I could get in to the new digs.

Then, I got creative. I called the local homeless shelter on Thanksgiving Day and spoke to a very nice worker there named Matt.

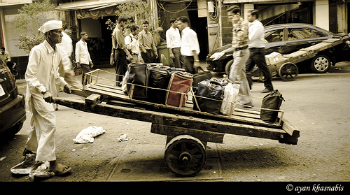

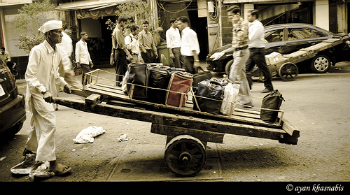

And that’s how I ended up the morning after Thanksgiving, driving a seventeen-foot Ryder panel truck carefully through my city’s sketchier downtown area, a block from the homeless shelter, looking for a group of homeless men who would be standing near a dumpster, Matt had said.

They saw me before I saw them, and they all ran towards the truck, shouting enthusiastically, some in broken English, and smiling at me.

This was a new experience. I wasn’t sure how I was supposed to proceed. Interview them? Ask for references? Draw straws? Fight club? A motherfucking walk-off?

I rolled down the window and held up two fingers.

“I just need two guys,” I said.

The first two guys that reached the truck hopped in and introduced themselves as Jorge and Luis.

Jorge spoke very good English – Luis understood me, but had trouble forming sentences of his own, so we slipped into an easy relay pattern where they’d converse in Spanish, then Jorge would relay a question to me, I’d answer, and Jorge would translate for Luis.

They had experience in moving; I could tell by the way they took a quick visual inventory and then started loading the heavy stuff – my second-hand mattresses (I know, ick) and the couches – into the truck first, and the efficient way they carried all the smaller stuff out and arranged it carefully.

And they were careful with my second-hand crap. Like they were all priceless antiques.

It took them three hours to empty the basement and unload it all into the cottage. It cost me $30 for each of those hours, plus an additional $10 tip to each of them at the end.

Parting with that $110 was the best fucking feeling I’d had in months.

The Aftermath

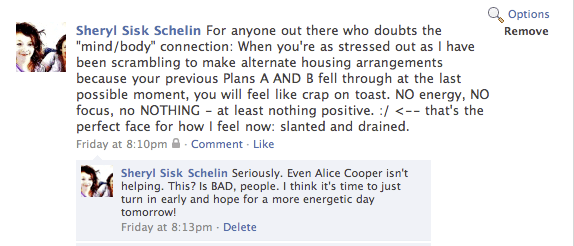

The day still took a crapload out of me, despite Jorge and Luis doing all the heavy lifting.

There were floors to be swept, trash to be picked up, bagged, and emptied, and last-minute packing of all the stuff we’d forgotten. In the new place, there were beds to be made, clothes to be unpacked, food to be arranged …

By the end of the day, I was hurting like I hadn’t hurt in a long, long time. Every muscle screamed, and my left leg was so nearly numb and useless that all I could manage were short, cane-assisted hobbles to the fridge and the bed.

And I continued to pay those dues the next day, too. All that Saturday, the pain throbbed in my neck and shoulders, and spread down to my calves and ankles. My back was one twisted, spasming knot of angry muscles.

But then something odd happened. The next day – Sunday – I felt better.

That’s two days after the massive, unusually strenuous exertion.

See, before the move, I expected to be bed-ridden for four days or more.

But there I was, Sunday morning. I was still hobbling and gingerly favoring a very sore back and leg, but I was up. And cooking breakfast. And unpacking.

I was functional.

Two. Days. Later.

I’m not sure mere words can describe how overwhelming that sudden infusion of hope felt to me.

For the first time in – well, years, I guess – I felt something other than resigned acceptance or bull-headed “I’m gonna have a good life despite the chronic pain” optimism in regards to my chronic pain experience.

It was the first time I felt it might be possible for me to heal.

Chronic pain – whether it’s from fibromyalgia, RA, ME/CFS, or any other illness – ought to be enough for any lifetime.

Chronic pain – whether it’s from fibromyalgia, RA, ME/CFS, or any other illness – ought to be enough for any lifetime.